“What Don’t Kill Will Fatten”: The History of Crucian Cuisine

Introduction

Ingredient for ingredient, flavor for flavor, authentic Crucian cuisine, the centuries-old culinary tradition of St. Croix, Virgin Islands, though little-known beyond the shores that give it rise, ranks among the world’s finest cuisines. And it is not uncommon for a visiting food guru or some Joe-Schmoe “foodie” to, upon tasting for the first time a bowl of proper Crucian kallaloo made with “papa-lolo,” “bata-bata,” “whitey Mary,” “bowah,” “pusley,” and scalded tania leaves (along with, of course, okra, eggplant, picked “pot-fish” [fish caught in fish pots], conch, purged land crabs, salted beef and pigtails, ham, and hot peppers); or boiled red snapper and fungi, the sauce flavored just so with the freshly squeezed juice of local limes, sprigs of thyme, salt and scotch bonnet peppers; or a plate of conch in traditional butter sauce, served with boiled sweet potatoes and green figs, the conch pounded then slow-cooked, not pressure-cooked as is the custom these days; or smoked-herring gundi, “salt-fish” [salted cod] gundi, or a luxurious seafood salad consisting, amongst other things, of whelks, lobster, octopus, and cuttlefish; or a seven-layer Crucian Vienna cake generously moistened with white wine; or a pâté not made to a johnny cake’s consistency but, instead, to a light, flakey, pastry texture, to declare those delicacies the absolute best the world over.

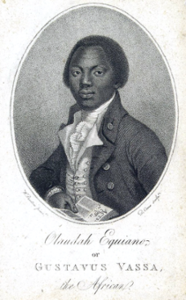

Crucian cuisine is the result of the native soil and the Afro-Crucian natives’ toil. Except for the ubiquity of cassava on the traditional table, very little of St. Croix’s culinary tradition can be definitively and distinguishingly attributed to the island’s pre-Columbian peoples. The enslaved West Africans who were brought to the island, beginning in the mid-1600s under the French and continuing into the 18th and 19th centuries under the Danes, however, are the people who laid the cornerstones and then constructed—ingredient by ingredient, dish by dish—what is today called “Crucian food.”

The Food of the Middle Passage

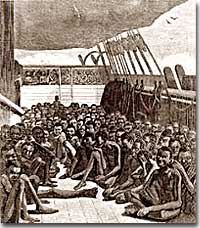

Meals were served twice daily: breakfast was dispensed around 10:00 a.m., and another meal in the late afternoon, around 4:00. In good weather, slaves ate in groups on deck; in inclement weather, meals were had in the slovenly holds of the ships. Slave groups/gangs were typically required to say grace before eating and give thanks after meals.

In order to monitor food-intake (and prevent slaves from deliberately starving themselves), the process of eating was sometimes directed by signals from a monitor who indicated when slaves should dip their fingers or wooden spoons into their bowls, and when they should swallow. It was the responsibility of the monitor to report slaves who were refusing to eat, the penalty for which was severe whipping and/or forced-feeding by use of a speculum orum, or mouth-opener, that was used to force food down a recalcitrant slave’s throat.

The typical slave-ship diet included rice, farina, yams, and horse beans. Occasionally, bran was included. Some slavers offered their slaves the so-called “African meal” once per day, followed by a “European meal” in the evening, which consisted of horse beans boiled to a pulp. Most Africans so detested the European meal that, given an opportunity, they would oftentimes surreptitiously throw it overboard rather than eat it.

Slaves from the various slave regions of West Africa had their food preferences: Those from the Winward coast tended to prefer rice; while those from the Niger Delta and Angola preferred manioc (cassava), though it was bulky and had a lower shelf life (unless in dried, flour form) and was therefore less frequently offered. “Slabber sauce,” comprised of palm oil, water, and pepper, was sometimes added to the food—to the relative delight of the slaves since palm oil was a popular ingredient in West African cuisine.

For drink, slaves were provided half a pint of water twice per day. Occasionally, pipes were circulated, affording each slave a few puffs.

Log books were carefully kept of ships’ provisions so as to avoid shortages at sea. When inclement weather in the Middle Passage prolonged a ship’s journey across the Atlantic, food and water allowances were reduced. In an infamous case in 1781, the slaving vessel Zong, headed to Jamaica, became short on food and water while also experiencing an outbreak of disease. The captain decided to jettison 136 slaves whom the captain argued were too sick or weak to recover, claiming that throwing those 136 slaves overboard spared them a lingering death.

[Primary Source: Edward Reynold’s Stand the Storm: A History of the Atlantic Slave Trade]

The Earliest Years

Though the French—from 1650 to 1695—brought enslaved Africans to St. Croix to toil upon the approximately 90 indigo, cotton, sugar, and tobacco plantations, most of which were situated along the island’s coastline, very little is known about French slavery on St. Croix, let alone the cooking-traditions of the period. What is well-documented, however, is that for the first decades of the Danish era—from the 1730s to the 1750s—whenever Africans were brought to St. Croix, they were provided with no food, clothing, or shelter. The slaves—men, women, and children—had to fend for themselves or starve to death, all the while toiling for their masters’ bounty.

“Empty sack can’t stan’ up.”

To eat, the already-exhausted slaves had to turn to the wild flora and fauna of their new tropical homeland: The African transplants had to rely upon land and sea to survive. And since, from the earliest years of colonization, the enslaved population outnumbered that of the Europeans, and since the European colonists tended to aspire towards European tastes and traditions, therefore preparing and consuming European foods (even if adjusted to accommodate the abundance of local ingredients and the paucity of European ones), it was the predominant Afro-Crucian cuisine that would come to distinguishingly define “Crucian food.”

The earliest Afro-Crucians, who were strategically extracted from various West African cultures so as to reduce the likelihood of organized insurrection, and who, from the moment of acquisition on the African continent were systematically cut from their African identities, had to look within themselves to collectively create a new food tradition—from scratch. Thus, Crucian cuisine was born.

Some foods, such as kallaloo, are clearly of direct, unadulterated African origin—as evidenced by the fact that the word “kallaloo” (or some variant thereof, such as “kalelu,” “calalu,” or “calelu”) is still used in some parts of West Africa and throughout much of the Afro-Caribbean to describe an okra-and-meat/fish-based, stew-like soup (perhaps most akin to Louisiana’s gumbo or Curaçao’s “yambo”).

Christian Georg Andreas Oldendorp, in his 1777 treatise titled History of the Mission of the Evangelical Brethren on the Caribbean Islands of St. Thomas, St. Croix, and St. John, provides a detailed description of kallaloo: “The Negroes call everything calelu [he also spells it “kalelu”] which they cook into a green vegetable stew from leaves and other ingredients. However, a really complete calelu, which the Whites and particularly the Creoles [in this case the word “creole” refers to island-born Whites] also like to eat, consists of okra, various kinds of leaves, salted meat, poverjack, which is a kind of stock-fish [presumably “wenchman”], kuckelus, a variety of sea snail [presumably “conch”], various fishes, tomato berries, Spanish pepper, butter, and salt. Along with the dish are eaten big soft dumplings made from cornmeal flour.” And describing kallaloo’s already-prominent place in local cuisine prior to his arrival on St. Croix in 1767, Oldendorp, presumably from written records and/or oral accounts describing mission-life on St. Croix in 1740, writes of the dish as he details the pioneering efforts of missionaries Friedrich Martin, Christian Gottlieb Israel, and Georg Weber: “They set up their cooking facilities in the regular Negro fashion. A dish called kalelu, or green cabbage, prepared from plant leaves and land crabs, which fortunately were plentifully available there, served as their daily fare in those days.” In essence, then, within a mere seven years after the Danish purchase of St. Croix from the French in 1733 for 750,000 livres, kallaloo had already emerged as so popular a dish amongst the local enslaved African population that it was already being consumed on a daily basis by European missionaries to the island.

But other local fare emerged on St. Croix from the ground up, whether as the result of a synthesis of West African culinary traditions; as the result of African and European confluence; or as the result of later cultural influences by major groups of immigrants.

“Eat alone, hungry alone.”

For the first hundred years of Danish slavery on St. Croix—from the 1730s to the 1830s, until the implementation of Peter von Scholten’s regulations—the workday of a plantation slave began at 4:00 a.m., when the bomba (foreman) would ring the plantation bell or blow a conch shell. Depending on the master, slaves would work until 8:00 or 9:00 a.m., at which point they were allowed a 30-minute break to eat breakfast, which they would bring with them from their slave quarters. After breakfast, work would resume until midday, at which point slaves were allowed one-and-a-half hours for lunch. Slaves with families typically would return to their quarters to eat, while single slaves tended to have their meal in the fields. After lunch, the slaves would work non-stop until sundown, at which point they were required to cut fodder for the plantation’s animals before returning to their homes to prepare dinner, eat, then ready themselves for the following day’s labor.

By the 1740s, Sunday (in addition to feast days of the Lutheran Church and royal birthdays), by consuetude, had become established as the day of rest for St. Croix’s enslaved population. And it was on that day that slaves had to attend to most of their private and personal matters: attending church services; cultivating their provision plots; buying and selling at the towns’ markets; washing and mending their clothing; entertaining themselves and each other; keeping house; visiting relatives; and, of course, cooking. But despite having very little free time, the slaves of St. Croix managed to produce a traditional cuisine that rivals any in the world.

“Wind chops and air pie…”

The Origins of Crucian Food

Of all the factors that contributed to the emergence of a distinctive, authentic, Crucian cuisine, provision plots; weekly rations of imported salted meat and fish, and cornmeal or cassava flour; the public markets; the interaction between free and enslaved urban negroes with the international white population; the island’s natural bounty; ironically, need and hardship; and the Caribbean’s tropical heat figure most significantly. And as a result, Crucian food is at once very African and very cosmopolitan: It is in many ways a microcosm of world cuisines. And, as such, Crucian food appeals to the palates of the world. “A Crucian cook,” it is said, “can feed the world from one pot.”

Provision Plots

By the 1740s, it had become the practice for plantation owners to devote a portion of their estates to “provision plots”: small subdivisions of land—typically about 30 feet by 30 feet—per slave family and single adult slave where they could grow their own mainstay crops such as okra, sweet potatoes, yams, cassavas, hot peppers, corn, bananas, etc. (And even today, when Crucians, as well as people throughout the Caribbean region, refer to “provisions” as a food group, they are referring to “ground foods” such as cassavas and yams and foods such as bananas that they would customarily grow on their provision plots.) On those plots, slaves, during their free time, would cultivate the food that sustained them. And it is upon those foundational ingredients that Crucian cuisine is firmly anchored.

Weekly Food-Rations

Beasts of burden must be fed if they are to perform at their optimum. Thus, one of the duties of the plantation slave was to provide food for the estate’s animals—before the slaves could provide food for themselves. Likewise, though not required by law, it became general practice for slave owners to provide food-rations to their slaves. King Frederik V’s Reglement of 1755, though never made official, specified that each slave 10 years and older was entitled to a weekly ration of two pounds of salted beef [and/or pork] or three pounds of salted fish, and two-and-a-half quarts of cassava flour or cornmeal (or three cassavas, each at least 2.5 pounds). Children under 10 were entitled to half those amounts.

Because of lack of refrigeration, coupled with the tropical heat, preserving meats with salt was essential. Salted beef and pigtails, as well as salted cod and smoked herring, were provided by slave owners; and those items became, and remain, the cornerstones of the protein component of traditional Crucian cuisine.

Corn and cassava, once converted into flour, are easy to store and enjoy an indefinite shelf-life, even in tropical conditions. So those ingredients figured significantly in the islanders’ daily fare. And while cassava flour is no longer a staple in the Crucian kitchen, cassava root and cornmeal certainly are. Cornmeal, the primary ingredient in the ever-popular fungi (also spelled “fungee”), a close relative of Italy’s “polenta” and Nigerian “foo-foo,” has always served—much like rice in China or pasta in Italy—as a relatively inexpensive way of providing a full stomach. When Queen Mathilde (1857-1935) of Fireburn fame died on October 10, 1935 at age 78 at the Frederiksted Hospital, her death certificate lists her official cause of death as pellagra, a disease that oftentimes visits upon people who rely upon corn as their primary food source.

The Public Markets

The island’s public markets in Christiansted and Frederiksted were by the 1750s well-established. But under Danish law, a slave was the property of his owner and could therefore own nothing. Thus, no slave could, in his own right, sell produce—not even that grown on his provision plot—in the public markets or even from his home.

“When people no like yoh, dem ah gih yoh basket foh carry water.”

The King Frederik V Reglement of 1755, the provisions of which could be wholly or partially implemented at the discretion of the governor, specified that slaves could only sell their masters’ goods in the public markets or as itinerant vendors (called “hucksters”). And to administer the proscription, two “inspectors” were posted at each public market to verify that each slave-vendor was authorized by his master to sell the goods he or she was offering for sale. But as was to be expected, the slaves routinely found ways to circumvent the policy in order to sell their own produce and earn money. And eventually, over time, the prohibition was relaxed, Sundays—primarily because it was the customary day of rest for the enslaved—becoming the market day for the island’s enslaved population. “Sunday Market” would remain a fixture in the island’s mercantile culture until 1843 when the market day for the enslaved population was switched to Saturday at the urging of the local clergy who complained that their converts would routinely opt to go to market rather than attend church services.

But whether held on Sunday or Saturday, and whether under the watchful eyes of “inspectors” or not, the public markets served as a crossroads for foodstuffs, socializing, and the inevitable exchange of culinary techniques, ideas, secrets, and traditions. The markets opened at sunrise and remained open until 8:00 p.m., vendors using candles to illuminate their selling-areas when darkness fell.

Danish West Indies scholar Neville A.T. Hall, in his seminal treatise Slave Society in the Danish West Indies, describes the offerings typically found at Sunday Market: “Vegetables such as cabbage, green pulses and tomatoes; peas; poultry, pigeons, eggs, yams, potatoes, maize, guinea corn and cassava, known locally as Indian provisions, pumpkins, melons, oranges, wild plums and berries from the hills of St. Croix’s north side; rope tobacco; cassava bread, which many whites, particularly creoles, were especially fond of; fish; firewood and fodder.”

St. Croix’s public markets—vegetable as well as fish—in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries (until ca. 1970) were bustling places, with demand driving supply, and supply driving demand, the end result being a consensus on the ingredients that would come to define Crucian cooking. [Two of the island’s earliest Black-owned storefront businesses, both established in the late 1800s, were provisions stores: the Bough store on Company Street; and the J.C. Canegata store at the corner of Company Street at “Times Square.”] The public markets and town galleries also served to unite the town and country populations: Herbs and spices grown in the countryside would season the pots of town folk, and fresh fish and imported goods would be carried home by the countryfolk. For decades, until the 1950s, Ann Richards Heyliger (1895-1963) would sell fresh herbs and vegetables grown at her Estate Pleasantvale (also called Pleasant Valley) property at the Frederiksted market, so much so that she would rent a room in the long-row that once ran immediately east of the market to store her supplies and produce when transporting them back to the northside at the end of the business day was not practical. The market was officially named in her honor in 1983. And until the 1940s, Catherine Batiste Messer (1892-1967) would every Friday morning deliver fresh produce from her Estate Annaly property to several re-sellers in Christiansted, the most notable being Ms. Marie Perry, who would sell under a gallery immediately west of present-day Harvey’s restaurant, and “Miss Jessie,” who sold from her spot in the vicinity of present-day “Times Square.”

Today, with the renewed interest in organically grown foods, the Christiansted and Frederiksted markets, as well as private and cooperative farmstands, are experiencing a renaissance as the island’s all-natural and “boutique” farmers such as Roy Rodgers, Mickey Peterson, Luca Gasperi, Percival Edwards, “Honey Man,” Nana Mary Lewis, the Jackson family, Dale Brown’s

“Sejah Farms,” and Nate Olive of “Ridge to Reef Farm” sell their produce directly to discerning customers who are becoming increasingly wary of genetically altered supermarket produce.

“Bring-come, carry-go.”

Interaction Amongst the Island’s Free and Unfree Populations

St. Croix’s free black population, which lived in the “Free Gut” and “Pond Bush” neighborhoods in the town of Frederiksted and the “Free Gut” and “Water Gut” neighborhoods in the town of Christiansted, also played a significant role in the development and evolution of Crucian cuisine.

The towns’ free black populations enjoyed the vibrant exchange of information occasioned when people cohabitate or live in close proximity. In such environments, recipes emerge, become generally accepted, then go on to become components of a traditional cuisine—the way words and proverbs become part of a language.

Likewise, the enslaved urban population lived in the “long-rows” and “big-yards” as support-staff for the towns’ finest residences. There, slave families lived collectively in village-like micro-neighborhoods that facilitated cultural, and thus, culinary, consensus. The urban slaves also had easier access to the wealthy kitchens of the towns’ elite, thereby becoming exposed to international cuisine, cooking-methods, and ingredients.

The Danish influence on what would become Crucian cuisine is undeniable: Salt-fish gundi and smoked-herring gundi are of Danish origin; fish pudding, prepared in a bain-marie and served with a delicate white sauce, is Danish; the traditional hard-candies, namely the peppermint-flavored “lasinja” (lozenge) and peppermint candy, and the Crucian answer to peanut brittle, “dondersla,” are of Danish origin. [Crucian coconut sugar cakes, however, are not; they are made in exactly the same manner throughout the tropical African Diaspora—from Ecuador to Brazil to Panama and Colombia to the Caribbean.] And the guava-based dessert, “red grout [with cream],” is a Crucian adaptation of the classic Danish dessert “rødgrød med fløde” (“red groats [porridge/pudding] with cream”), which is made from a combination of at least three red berries such as redcurrants, blackcurrants, raspberries, blackberries, strawberries, etc., and served with heavy cream.

The Island’s Natural Bounty

Long described as “The Garden of West India,” St. Croix, with its gentle terrain, is an island conducive to a wide variety of flora and fauna. When the French, the island’s first major colonizers, established their plantations on the island’s periphery in the middle of the 1600s, the island’s interior, with its primordial forests, was left intact. And when the Danes purchased the island from the French in 1733, nine years later found them still clearing the island’s lush forests in order to make way for sugarcane plantations. Several rivers, the vestiges of which reappear during the island’s rainy season, were recorded as permanent waterways upon the Danes’ arrival in the 1730s. Blessed by nature as a fertile land, St. Croix was generous to its inhabitants, bringing forth a wide variety of plants and animals that figured significantly in the evolution of Crucian cuisine.

Need and Hardship

Despite the island’s bounty, however, life for the enslaved population was harsh, oftentimes reduced to a hand-to-mouth existence. Governor Philip Gardelin’s slave code of 1733 could best be described as draconian: A slave had no rights—not even to life itself. Governor Moth’s 1741 “Articler for Negerne” was simply an elaboration of Gardelin’s Code, and Governor Lindemark, Moth’s successor, went even further in spelling out what slaves could not do and what would be the consequences for doing that which was proscribed. Only with King Frederik V’s Reglement of 1755 is the notion of slaves’ rights introduced: rights to a slave dwelling; weekly food rations; access to provision grounds; one free day per week to tend to provision grounds; approximately five yards of coarse fabric to construct garments; a hat every two years; and care when ill and/or elderly. But even then, the regulations were hortatory, not mandatory, since, in reality, the exceedingly harsh Gardelin Code was never repealed or officially superseded—until the slave laws enacted in the 1830s during the Peter von Scholten administration. Yes, after the 1750s, slaves were permitted to marry—with their masters’ permission. But even within the context of Christian matrimony, the ancient Roman concept of partus sequitur ventrem [Literally, “that which is brought forth follows the womb”] was practiced: The child of an enslaved woman was automatically a slave owned by its mother’s owner, even if the father was free and married to his enslaved wife.

As the decades of the 1700s went by, custom came to dictate that slaves could earn money during their days off, some accumulating enough to purchase their freedom and that of their loved ones (as well as whatever they could afford at the public markets). And by the 1780s, slave children could receive basic public education in reading and writing, the Danish West Indies thereby becoming the first place in the history of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade to allow for the public education of slaves. (And those basic skills facilitated the reading and writing of cooking-recipes.) But, relying upon the 1733 Gardelin Code, which remained on the books for a century, some plantation owners would—with legal justification—invoke the harsh provisions of the Code.

It was in that environment, then—one where a slave, technically, did not even own the food he produced on “his” provision plot—that the slaves of St. Croix eked out one of the world’s great, even if relatively unknown, culinary traditions.

Except for the towns of Christiansted and Frederiksted, St. Croix was almost entirely subdivided into privately owned plantations. As such, there were no public or “no-man’s” land for a slave to hunt for game. Even fruits—except for those gathered from trees growing on the public roadsides—belonged to whoever owned the land upon which the fruit-bearing tree was situated. Therefore, a slave carrying a sack of fresh fruit could be questioned as to the origin and ownership thereof. The Caribbean Sea, however, was an entirely different matter. No one owned the sea; and no one owned its bounty. A slave en route to his home with fresh fish that he caught in the sea did not have to account to any man. And what was particularly appealing about fresh fish was that fish were free of charge and required no husbandry. So besides being an excellent source of protein and other dietary essentials, it is quite understandable why fish, to this day, occupies a place of honor in Crucian culinary tradition.

But besides the vast array of fresh, luxurious-by-today’s-standards seafood that was readily and plentifully available to the local population [It is said that lobster was so plentiful until the 1940s that it would routinely be used as bait.], Crucian cuisine is also built on a foundation of things discarded or undesirable: pigs’ feet, ears, and snouts for “souse” (there is also a pigtail souse); the cloven hoofs of cattle for “bull foot soup” and the unwanted tail for “stewed oxtail”; animal entrails for “tripe soup”; stewed cattle’s tongue; and pigtails for everything from “red peas soup” to “seasoned rice” to “crab and rice.” Crucian cooks, like their counterparts in the southern United States who turned chitterlings and fried chicken into delicacies, picked up the throwaway portions of butchered animals and skillfully and ingeniously transformed them into world-class food.

While the New World white population was preoccupied with trying to emulate Europe, the New World black population, which had been cut off from Africa and denied any knowledge of her, had to look within its displaced, disconnected self to reconstruct a new culture. In North America, that reconstructed culture came to define that which is regarded as authentic American culture: blues, jazz, rock-and-roll, and soul food, for example. On St Croix, the culture emerged as “scratch-band music” (now being called “quelbe music”); carnival, and Crucian food.

It is also need and hardship that led to boiled green bananas, locally referred to as “green figs,” becoming major players in the cuisine: A mother with children to feed but nothing with which to feed them, in utter desperation, decides to boil a hand of green bananas, only to discover that the unripe fruit, when boiled, has a texture and flavor somewhat like potatoes or cassava. Today, boiled green figs are a welcomed Crucian delicacy, whether served plain as a side-dish to fish or meat with a sauce, or as guineitos, a recipe adopted from the Puerto Ricans and people from the Dominican Republic, where the boiled greens bananas (a little milk added to the water to maintain the fruit’s creamy color) are sliced into “wheels” and pickled with vinegar, onions, oil, olives, and bell peppers. In years past, in time of severe need, Crucians would also eat boiled green sugar apples as a vegetable-like side-dish, a custom long-disappeared on St. Croix but still practiced on the British Virgin Island of Tortola.

“Hungry dog eat raw meat.”

Cooking-Facilities

Until the 1840s, most plantation slaves cooked on outdoor fires, presumably on the traditional “three-stone” fires, since slave dwellings, except for those situated on the 16 estates belonging to the Danish crown, had no kitchens. [According to Neville Hall, The Royally Leased Estates—“Kongelige Forpagtede Plantager”—required that lessees of those plantations build slave dwellings thus: “houses were to be high, airy, wooden floored with masonry walls, shingled or tiled, partitioned in two, with minimum measurement of 18 feet by 12 feet and with a separate kitchen”]. In inclement weather, cooking was done inside the homes, which almost always had earthen floors.

In 1838, when the Peter von Scholten administration called for improved slave housing, some efforts were made to upgrade the typical slave dwelling, which traditionally had been constructed of wattle-and-dab walls with cane-trash roofing and no kitchens. But for the most part, most slave dwellings, and, thereafter, plantation tenement dwellings, remained substandard—even if kitchens became more prevalent as part of the governor’s housing initiative.

With kitchens came a transition from outdoor “three-stone”-cooking to indoor coal pot-cooking. Local tinsmiths made pots and pans, sometimes from discarded tin cans, and indigent Crucians ate and drank from calabash gourds and simple tin utensils. By the 1920s, most people—even the poorest of the poor (hence the saying, “Yoh ain’ even got a pot to piss in”)—possessed a cast iron pot for frying fish and johnny cakes; a large-sized pot for cooking kallaloo; a long-handled pot for turning fungi; a rice pot; and two pots designated for the exclusive use in the making and “tossing” of maubi, a low-alcohol-level, homemade beer that is brewed from maubi bark, herbs, and roots and drunk throughout the Caribbean region.

Makeshift Ovens

In the plantation villages and “big-yards” of St. Croix, Crucian cooks, from the middle of the 1800s, would do their baking in makeshift ovens. The tin pans in which kerosene oil was imported, when emptied, were transformed into ovens that could bake everything from breads to pound cakes to fish pudding.

The kerosene pan was outfitted with a “rack” made of several rows of a sturdy twine or wire threaded horizontally across the width of the tin pan, and a sliding- or drop-door closure made of a sheet of tin. The makeshift oven would then be placed atop a coal-filled coal pot. When the appropriate interior heat was attained, the baking-pan containing the item to be baked would be placed atop the rack and the door shut. Upon completion, the baked item would be removed from the oven, the oven set aside for future use. By the 1940s, Crucians were using kerosene stoves and ovens. Only the elderly held on to their traditional coal pots. And the popular saying, “Ah come foh ah stick o’ fire,” meaning that a person was stopping by for a very short visit (just enough time to get a stick of fire then run back home with it, still ablaze, in order to ignite his own fire) fell into disuse. By the late 1950s, cooking was generally being done with propane gas ranges. And it was about that time that the saying, “Cooking with gas…” entered the vernacular, its meaning being that “Things were going well.”

The Island’s Warm Climate

Refrigerators are a relatively recent invention. And in the tropical heat, cooking-methods had to be implemented and sometimes invented such that food would be preserved. Until the 1960s, when many Crucians still lived in “big-yards,” “long-rows,” and plantation villages, it was customary for people who had no icebox or refrigerator to preserve fresh cuts of meat by “corning” them—salting then sun-drying. The island’s salt ponds served as a source for large quantities of salt: At certain times during the year, when portions of the salt ponds would naturally dehydrate, people would harvest the salt for culinary uses. Such methods and practices informed the cuisine.

Key Ingredients and Methods of Crucian Cooking

Vinegar

In the hot tropics, long before iceboxes and refrigerators became household appliances in the island’s finer homes beginning in the early 1900s in the case of the former and by the 1940s in the case of the latter, vinegar was, and remains to this day, the Crucian cook’s first line of defense. All meats—whether home-slaughtered, obtained from a professional butcher, or FDA-approved and supermarket-bought—prior to being seasoned, are washed in a solution of cool water and vinegar, thereby ridding the meat of surface-bacteria while imparting a refreshing scent to the meat. (Fresh lime juice, especially when preparing fish for cooking, may also be used.)

Vinegar is also a key ingredient in many of the cuisine’s tomato-based sauces. No Crucian cook would make a fried-fish sauce without vinegar, which serves to both flavor and preserve the dish.

And a Crucian potato salad, the traditional complement to souse, will never taste “Crucian” without vinegar (which also serves to preserve the mayonnaise in warm temperatures).

“Feed um wid a long spoon.”

Seasoning-Salts (“Dry-Rubs” and “Seasoning-Blends”)

The mortar and pestle is an indispensable component of the Crucian kitchen—so much so that it has been immortalized in Crucian proverb: “There is more in the mortar than the pestle.”

Unlike many Caribbean islands, such as Jamaica, Puerto Rico, and Trinidad, that use paste-like seasoning-bases made from finely chopped or puréed fresh herbs and spices, the seasoning-base of Crucian cuisine is the “pounded-seasoning” or “seasoning-salt” referred to in the U.S. mainland as a “dry-rub,” additional herbs and spices, fresh and/or dried, being added, if desired, to the dish thereafter.

Seasoning-salts are particular to each family; there is no one recipe—the way Indian families have their own curry or garam masala blends. And even within families, the ingredients are added “by hand” rather than per measuring-spoon. Generally, however, seasoning-salts begin by pounding fresh garlic with coarse salt in a mortar and pestle. Thereafter, black pepper, paprika, and other dried herbs and spices are added and pounded.

The proportions of the ingredients also change, depending on the intended purpose of the seasoning-salt. For example, the proportion of cloves will traditionally be increased for a seasoning intended for goat meat, while cloves will be eliminated for a seasoning intended for fish. A seasoning for pork will rely heavily upon garlic and black pepper, whereas the seasoning for lamb would incorporate dried mint leaves and extra rosemary.

Because of the salt-content and the use of primarily dry herbs and spices, Crucian pounded-seasonings, unlike the paste- or purée-like seasonings of the other islands, are not refrigerated and enjoy an indefinite shelf-life if kept in a tightly sealed container and stored in a cool, dark, dry cupboard.

Unlike many European cultures where meats are seasoned mainly with salt and pepper added just before, during, or even after cooking, Crucians tend to pre-season or dry-marinate cuts of meat and fish with sophisticated seasoning-salts for as few as 30 minutes in the case of fish or chicken, and up to 24 or even 48 hours in the case of large game meats such as turkey, duck, guinea fowl, mutton, venison, and boar.

Crucians regard very few commercially available seasoning-salts as being comparable to their homemade counterparts. But when a high-quality commercially packaged seasoning-salt is identified, it is readily used as a cost-effective, time-saving substitute since purchasing individual containers of the numerous dry herbs and spices required to make the traditional seasoning-salt blends can be financially burdensome to people of modest means.

The Principal Ingredients for Savory Dishes

Crucian cuisine, like most traditional cuisines the world over, is fundamentally simple, centered around a few, key, flavor-imparting ingredients: salt; thyme and “chibble” (green onions, spring onions, scallions, chives); fish and meat stocks; fat pork (fatback); butter; limes; hot peppers; black pepper; garlic; cooking oil, locally referred to as “sweet oil”; onions; vinegar; and tomatoes (the fresh fruit, the paste, or the sauce).

The Major Sauces and Gravies

There are two everyday sauces: The classic Crucian butter sauce that is made of fish stock, onions, fresh lime juice, hot scotch bonnet peppers, butter, thyme, and salt to taste (Garlic is optional); and the classic Crucian red sauce, used to complement fried fish, for making stewed fish, or when making stewed salt-fish, the sauce begun by “melting” fat pork (fatback) in a hot skillet, then adding onions, tomatoes (the fresh fruit, sauce, or paste), thyme, fish stock or water, hot peppers, black pepper, and vinegar. (Green peppers and/or “Puerto Rican peppers” are optional. And if additional oil is desired, it is obtained from the remaining oil in which the fish was fried, or, in the case of stewed salt-fish, added from the container of vegetable oil or olive oil).

A more sophisticated sauce (in this case called a gravy) is traditionally made to accompany game meats. Giblets—the heart, liver, kidney, and gizzard (in the case of fowl)—are slow-boiled with what is referred to in the Cajun cuisine of Louisiana as the “the holy trinity”: onions, celery, and green peppers. To the stock derived from the organs and vegetables is added the finely diced organs, the pureed vegetables, a flour-and-butter roux, and various herbs and spices.

Evidence of an Established Cuisine

By the 1850s, a little more than a century after the Danes purchased St. Croix from the French, a distinctive Crucian cuisine had already taken shape. Perhaps the best written record of that cuisine exists in the personal missives of young Danish schoolteacher Johan David Schackinger who, on board the vessel Triton, arrived at the port of Frederiksted, St. Croix, on July 25, 1857, to serve as First Teacher at the Frederiksted Dane School (then called “Citizens and Common School”) on Prince Street. Except for two classrooms on the upper level of the school’s stately edifice, one for boys and one for girls, the rest of the floor served as Schackinger’s residence. His cook was a female mulatto named “Fanny.” (Almost a century later, in the 1930s and ‘40s, Mercedes “Mamita” Harris, mother of Tino Francis, and Regina “Jenny” Samuel, grandmother of former lieutenant governor of the Virgin Islands Vargrave Richards, cooked at the school.)

From his arrival in the Danish colony until his untimely death in 1863, Schackinger wrote a series of letters to his family back in Denmark, vividly describing his life on St. Croix. Fortunately for Virgin Islands history, the family preserved and then donated the letters to the Danish National Museum. In 1998, Danish West Indies scholar John H. Mudie, a descendant of one of St. Croix’s old and esteemed colonial families, with the aid of Lotte Alling Garcia, a Dane then living in Puerto Rico, translated the letters, Mudie thereafter publishing them in a book titled St. Croix Alive At Mid 19th Century[:] True Story of a Young Danish Schoolmaster in St. Croix for 6 years (1857-1863).

A few days shy of a year after arriving on the island, in a letter to his parents dated July 1, 1858, sent to Denmark enclosed in a package the contents of which were secured within a hollowed-out calabash, Schackinger describes the exotic items in the parcel: a jar of “tamarind jam”; a jar of “guava gel,” which he describes as very savory; some “pigeon peas,” which he says grow everywhere on the island and “in a white sauce they are a common dish for all inhabitants.” Schackinger, apparently very fond of pigeon peas, cautions his parents that they could perhaps only grow in Denmark in a greenhouse, but suggests, nonetheless, that his parents “put some of them in the garden or in a flowerpot and eat the rest.” (He also enclosed in the package some inedible items as curiosities: “pumpybeads” [presumably “jumbie beads”]; “some bigger grey balls by the name of “nickars” [also locally referred to as “nickal” and “burn-burn”]; and some “red pearls or seeds, the so-called ‘cokricoos’” [possibly “annatto”].)

Schackinger then proceeds to describe the island’s bounty, his spelling, apparently, phonetically derived from his understanding of the native tongue:

A lot of fruits are found here in this country that far exceed the Danish fruits in beauty and in tastiness; of these I shall just mention “pineapple” or “ananas” whose rich taste of course is well known; “alligator-pear” whose flesh looks like marrow and is eaten with salt and pepper, “cashew,” “mangrove,” [presumably “mango”] “guava,” “mammee,” “soursop,” whose flesh is plump, nutritious and quenching, “sugar-apple,” “sweet oranges” or oranges, “shadock,” that grows high and bears a fruit the size of a child’s head, “grenadilla,” which carries yet a bigger fruit, and is considered one of the most delicious in the world both in fragrance and taste, “bell-apple,” which in taste has a similarity to gooseberry, “melon,” “Yuma,” [presumably “yam”] “pannier,” [presumably “tania”] “sweet potatoes,” “pimkin,” [“pumpkin”] “tomato,” “coconut” and the “plantane-tree” or banana tree, which is often planted in long rows like groves called “banana walks.” A tree whose stem consists of a fleshy layer outside another often reaches a height of 16-20 feet and carries a whole cluster of fruits, “pisang,” which not only are nutritious and tasty when roasted or in a white sauce, but when raw it is a very pleasant food and one of the principal articles of food for the Negroes.

“Monkey know which tree to climb.”

In a letter to his parents dated February 10, 1859, nineteen months after first arriving on St. Croix, Schackinger, now more cognizant of the gastronomical ways of the island, writes thus:

Compared with the way of living in Denmark, the West Indian way is undeniably much more fashionable, but generally also more extravagant. Here we eat much the same sort of meat as home; besides tortoise, guinea fowls and a lot of turkeys, etc.

The ocean has a large abundance of fish, some edible, others poisonous. Of the edible ones I shall only mention “king fish” which makes a wonderful dish, “hog fish,” “grouper,” “pew fish,” “barracuda,” “Spanish mackerel,” “cavallo” [covalli ?], “flying fish,” “seabat,” “sea devil,” “oldwife,” “trunk fish,” “porcupine,” “parrot fish,” and “sprats”; also we find a lot of sharks, besides lobsters and sea and land crabs etc. etc.

Turtle soup, “white bean soup,” “calalu” (the Negroes’ usual meal), different so-called creole soups, among them “guava soup,” “cucumber soup,” are eaten here, and many other kinds that I hardly know the names of; the only thing I know is that nearly all of them are mixed with hot spices, especially with different kinds of pepper that grows here.

“Pigeon peas” are boiled in water with pork and potatoes, onions, thyme, etc. The green “pigeons” are much better than the dried, but unfortunately they cannot be sent home to you.

Further, bread which is nearly always based on wheat is eaten here just like at home; oil is not used for bread, only butter, which anyway when it has been melted by the heat looks like oil.

Although I could live here as a squire, my way of living is simple, because after all I am bored with all these fine and delicious courses that one is treated to here. When I can get some nice salt herrings and Danish potatoes with melted butter and pepper, then I prefer that to roasted turkey, guinea fowls, etc. Besides, it is my opinion that in the long run it pays to live a simple life and one will feel well. The most common drink here is “grog” and nearly all kinds of wine.

“When guinea bird wing bruck, he walk wid fowl.”

The Role of the Greathouse and Town-Mansion Cooks

While it is irrefutable that traditional dishes such as kallaloo, maufé, and souse are of Afro-Crucian origin, other equally native delicacies, like fish pudding, potato stuffing, Crucian Vienna cake, and pâtés, are arguably the creations of Afro-Crucian cooks charged with the preparation of dishes to satisfy the local European palate. And the cooks so charged were those in service in the kitchens of the island’s many greathouses and wealthy townhouses. Fish pudding, for example, which employs the bain-marie method, is clearly a dish rooted in the European tradition; but its obligatory usage of local blue fish (sago) and pink fish (parrot fish), along with local “pounded seasoning,” hot peppers, and thyme, is unequivocally the “hand” of local cooks. Similarly, while sweet potatoes were one of the cornerstones of the everyday fare of the enslaved population, white “Irish” potatoes, which do not grow locally, were imported for the island’s European population. And it is those white potatoes that became the obligatory potato for the revered Crucian potato stuffing, which was “Africanized” by local cooks who added sugar, tomato sauce, seasoning-peppers, onions, thyme, hot peppers, and a handful of raisins for flair. The dish that emerged from that African culinary input would go on to become one of the defining dishes of Crucian cuisine. Likewise, the luxurious Crucian Vienna cake is a delicacy that, because of its cost and manner of preparation—incorporating refined white sugar, copious amounts of butter and eggs, layers precisely sliced with confectionary implements, and imported white wine—was clearly a dessert that emerged from the island’s wealthiest kitchens, not the island’s plantation villages or “big-yards.” But since the cake is baked nowhere else in the world—not even in Vienna, Austria—it is almost certain that its culinary uniqueness, coupled with its age-old local ubiquity, is the result of Afro-Crucian influences. And while the “empanada” and various other meat-filled pastries are known throughout the world, the Crucian pâté, with its delicate, flakey, pastry outside and peppery meat fillings, is decidedly African-inspired though not African in origin.

The greathouse and wealthy townhouse cooks, with their access to the scarce, eclectic, and expensive ingredients made available to them by their wealthy masters and employers, played an invaluable role in the evolution and elevation of Crucian cuisine.

The Presentation of Crucian Food

What is today classified as “Crucian food” is, for the most part, the everyday food of the enslaved, and thereafter of the emancipated, labor-class of St. Croix.

Unlike many other cultures, where food is served in successive courses, each in a designated dish, Crucians, like most other Caribbean peoples of African descent, put what would normally comprise the various courses of a meal—appetizer, salad, and main course—onto one plate, all at the same time. Even in the case of soups, traditional Crucian soups are hearty soups (as opposed to consommés, purées, and creams) that are intended to be eaten, not as one course of several, but as an entire meal in and of itself. Thus, when a Crucian soup—be it red peas soup, bull foot soup, or chicken soup (best when made with purged, yard-raised chickens), for example—is served in its big bowl, it is the only dish served, with, perhaps, a dessert served thereafter.

For much of St. Croix’s history, eating was a means to a nutritional end, not an occasion for delightful relaxation. Food had to be solid and eaten quickly so that it would sustain people as they engaged in backbreaking labor in the island’s sugarcane fields. Slaves had to eat quickly then return to their work. And even on Sundays and holidays, cooking and eating had to take place in the midst of attending to other personal matters.

The practice of eating meals in separate courses with short breaks between courses was simply unsustainable for labor-class Crucians; it was a simple pleasure that they simply could not afford. Besides, the additional dishes, even if calabash gourds (called “gobi” and pronounced “go-bee” on the island), would have to be washed after meals, thereby adding to the already-colossal workload of the sugarcane workers.

It is within that historical context, then, that even today the one-plate custom endures in local “cook-shops” and in restaurants that cater to a local clientele. In the island’s many international restaurants, and at private dinner tables hosted by Crucians who have lived and traveled abroad, however, meals are increasingly being served in separate courses, each in a designated dish and with a complementary wine.

“One-one guava full up basket.”

The Need for the Preservation of Crucian Culinary Culture

The culinary tradition the Danish schoolteacher describes in his elegantly written letters predates the 2017 Centennial Celebrations by 160 years. And based on the rich archival record he left behind, much of the cuisine has remained intact, but much has also been lost to time. Thyme was then, and is now, the most prominent herb in Crucian cooking. But the guava soup and cucumber soup once favored by the island-born white population are no longer locally served. Turtle soup, regularly eaten on St. Croix until the 1960s, is today not served on account of protected species laws. But even the once-ubiquitous white sauce that was the complement to pigeon peas has disappeared without a trace. What ingredients were used in that popular, everyday sauce; how it was made; and what was its flavor-profile have faded from the popular memory. The moral of the story, then, is that even something as fundamental as everyday dishes must be specifically preserved, lest they be forgotten. And special preservation protocol should be established to ensure the perpetuity of the dishes that are unique to Crucian cuisine.

All things considered, a proper Crucian kallaloo is the world’s best kallaloo. The Crucian Vienna cake, baked only in the U.S. Virgin Islands, is the world’s most delicious cake—if made correctly. No other cuisine makes a potato stuffing that can rival that of St. Croix. The word “souse” can be found in Webster’s Dictionary, and other cultures have variations of souse, but none can match the taste of properly made Crucian souse such as that made each Tuesday until the late 1960s by Mrs. Hosanna Balfour Gittens of Queen Street, Frederiksted. Jamaica has “patties” and Latin America has empanadas, but neither can favorably compare to an authentic Crucian pâté, such as that of the late Delita Eastman of Queen Cross Street, Frederiksted (who mastered the art of making pâtés and the traditional candies while under the tutelage of her mother, “Miss Ella”), in texture and flavor. Presently, the commercially available pâté that comes closest in taste and texture to the authentic Crucian pâté is the Puerto Rican-influenced pâtés of Rosalia Ayala, who for decades has been selling the delicacy from her Rosa’s Booth, directly across from the ballpark at Estate Whim. (The late “Burulun,” also of Puerto Rican heritage, had mastered the authentic Crucian pâté in all respects, but, unfortunately, his technique went with him to the grave.) Maufé, bridesmaid to kallaloo and cooked only on St. Croix, is barely known today—even on St. Croix.

While johnny cake-type fried breads are known the world over, whether called “arepas” or “fried dumplings” or “johnny cakes” or “gnocco fritti,” very few people realize that traditional Crucian cooking boasts two, not just one, johnny cakes: a simple one, made primarily of flour, water, shortening, and salt and is more akin to the Puerto Rican “arepa,” which is eaten as a complement to a meal; and the more complex johnny cake, made with flour, milk, water, eggs, shortening, sugar, a pinch of salt, vanilla essence, and a dash of nutmeg and cinnamon, which is eaten as a substitute for a full meal. Eastern Caribbean-born Agnes Singleton, who used to fry those old-time, “full-belly” Crucian johnny cakes (with the option of sprinkled-on sugar) in the old stone kitchen at the Whim Greathouse until the early 2000s, was the last person making them for public consumption on St. Croix.

The Crucian “whelks in butter sauce” is unparalleled—head and shoulders above the stewed variety prepared in most other places, where the tomato sauce, garlic, and spices used therein completely dominate the delicate, but intoxicatingly delicious, flavor of the whelk itself. Conch—pounded and slow-cooked, not rapidly pressure-cooked—is almost a thing of yore. But traditional Crucians know that to pressure-cook conch is to kill it a fast death, transforming it from “fruit de mer” (“fruit of the sea”) to “caoutchouc comestible” (“edible rubber”).

Traditional Crucian tarts, such as those once made by the late Maria Nichols Thomas, are correctly made with a light, flakey (almost cookie-like), butter-rich crust, not with the heavy, bread-like shell that immigrants, apparently too falsely proud to learn the old Crucian way, created in a failed attempt to duplicate a native classic. And while on the delicate topic of tarts, many present-day bakers do not know that the preferred filling for the Crucian tart is not jams or preserves (the guavaberry tart being the exception), which are, for preservation purposes, prepared with high quantities of sugar. Instead, since tarts are traditionally kept in pie safes and consumed on the day of or within days of their preparation, the fruit-fillings for tarts are prepared with much less sugar than their jarred preserve counterparts, thereby allowing the actual flavor of the fruit to be featured. (Only when fruits are out of season are preserves used—as a last resort.)

Traditional Crucian pastries such as “royal” (a cross between a bread and a spice cake and regarded as a “poor man’s cake”), in years gone by the specialty of the late Florence Pedro, and the ginger-flavored “horseshoe,” are unlikely to be known by islanders born after 1964, the descendants of Evadney Neazer Peterson being amongst the few who still know how to properly make those delicacies. Crucians who attended the Mother of Perpetual Help Chapel at Estate Montpellier would recall “Miss Baby,” godmother of Ralph George, selling royal and horseshoes after Mass each Sunday under the still-standing tamarind tree on the roadside across from the chapel. Laura Moorhead’s cookbook, Krusan Nynyam for Mampoo Kitchen, has what is believed to be the only surviving recipe for “royal,” also called “royal cake.”

“Monkey don’t know how big he asshole bih ‘til he swallow pommecythere seed.”

And today, for a Crucian to get a proper “lasinger” (a corruption of “lozenge”) or a circular peppermint candy with the red peppermint drop centered on top, he must go to St. Thomas (where “lasingers” are called “jawbones”) to get it from Mrs. Lucia Henley, one of the few people in the Virgin Islands who still know how to correctly make the traditional local candies, donderslas included. “Miss Delita” Eastman was one of the great “candy ladies” of St. Croix, her specialties being “lasingers” and “donderslas.” Mrs. Irene Stewart Ferdinand was also a sought-after “candy lady,” her favorite selling-spot being the same tamarind tree at Estate Montpellier, sitting alongside “Miss Baby.” Frederiksted’s Mrs. Maria Edwards, wife of one-armed Arthur “Cosho” Edwards, was also highly esteemed for her local candies. In Christiansted in the 1930s, “Leoneale” Harvey was revered for her candies, pâtés, quelbe tarts (the traditional name for the fold-over, half-moon-shaped tarts that are about the shape and size of a pâté), etc., would sit under the gallery of what is today Harvey’s Restaurant, selling her delicacies atop a tray. Today, Laverne Bates of St. Croix makes a traditional dondersla, and she can usually be found selling her products at cultural events.

The Crucian perilee is a whole other matter: It is, for all practical purposes, lost to Virgin Islands culinary history—unless its recipe was preserved by the descendants of George Moorhead, Jr., (1894-1971), father of Esther Moorhead Urgent, known for his perilees as well as for his hand-shaven fracos; and Cuban-born Sidesair “Cubano” Bastian of Frederiksted, son of Steven Bastian, brother of Sidney Bastian, and father of Marion Bastian Plante. [The perilee is a hard-candy, sometimes studded with anise seeds, with origins in the Spanish Caribbean and brought to St. Croix, it is believed, by Crucians who had traveled to the islands of Cuba and the Dominican Republic as sugarcane laborers in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

A flat sheet of board would be perforated with evenly spaced holes, each about the diameter of a penny. Wax paper would then be rolled into tiny cone-shaped cup-molds and inserted into the holes. The hot syrup of the candy would then be poured into each wax paper mold and allowed to cool into a hard candy. As a convenience to children, in the olden days, a tiny holding-stick made of the clean-shaven spine of a coconut palm frond would be inserted into the candy in its semi-hardened state. Mr. Moorhead’s perilee-making used to take place at the end of Queen Street in the Pond Bush neighborhood, across from the Steinmann house. (The Pond Bush neighborhood has been replaced by the Lagoon Street Homes and the Virgin Islands Legislature Complex.) First, Mr. Moorhead sold his perilee candies from a pushcart. Thereafter, he established a candy store in the Pond Bush neighborhood.]

Before commercial popsicles became readily available from every “corner-shop” with an on-site refrigerator, Crucian children, on their way home from school on a blisteringly hot day, would treat themselves to a “lindy” (called “special” on St. Thomas) or an “ice pop,” the former being a juice-drink frozen in an ice tray and sold as individual cubes, and the latter a fruit juice frozen in a cup along with a popsicle stick. While Mr. James Graham (1915-2003) was Christiansted’s “Fraco Man” [In some islands “fracos,” also known as “snow cones,” are topped with condensed milk, but that tradition has never been widely practiced on St. Croix.], Mrs. Maria Edwards [Gibbs] Pinder was that town’s go-to person for lindies and ice pops. The wives of the locally famous musicians Archie and Wesley Thomas were the go-to’s for both treats in Frederiksted. Today, now that household refrigerators with freezers are commonplace, the lindy- and ice pop-seller is a thing of the past: Children simply make their own in their household freezers. Fracos, however, are still sold by street-vendors at public events ranging from horseraces to outside the cemetery gates at funerals. But long gone are the pushcarts transporting large blocks of Hennemann ice that would be manually shaved with hand-held ice-shavers. Instead, pickup trucks carrying automatic ice-crushers are used by today’s “fraco men”: Gladstone Browne, who has lived on St. Croix since 1962; Easton “Ras X” Brookes; and Lesley Farrelly.

Up to the 1960s, gooseberry stew (called “stewed cherries” on St. Thomas) was not sold in a cup; instead, the berries were speared onto the spine of a coconut palm frond, a tradition kept alive by Mrs. Lucia Henley on St. Thomas. And tamarinds were rarely stewed (preserved with sugar) when fully ripe, as is the custom today. In times past, the half-ripe “flurry” (floury) tamarind, fat with pulp, or “full” green tamarinds, blanched for easy removal of the skins, would be stewed into one of the island’s favorite preserves. And they, too, would be skewered onto the spines of coconut palm fronds.

Crucian “millennials” think that a “tamarind ball” is simply made by shelling ripe tamarinds and rolling them, along with copious amounts of sugar, into golf ball-sized balls. Little does that generation know that a true tamarind ball, about the size of a “bolongo” marble, is made by painstakingly scraping the pulp away from the fiber and seeds, then rolling only the pulp, with sugar, into balls, a delicacy still, and perhaps only, made by Ms. Angel Ebbesen Wheatley of St. Thomas.

Unless special efforts are made to document—even with mobile phones—the proper way to “toss” maubi and to make soursop tisane, those traditional drinks, too, will be lost or so altered as to render them unrecognizable.

Were it not for Lithia Brady, daughter of Mary Messer, Crucians born after 1969 would not even know what “lime asha” is, let alone that it is one of the world’s great delicacies. When St. Croix-born (of St. Thomas parentage) fashion model Lisa Galiber (1960-2011) tasted lime asha for the first time in 2010, she declared it “absolutely delicious!” and bemoaned not having known of it all her life.

And if old-time Crucian bakers such as the late Vivie Lockhart of Frederiksted and Ione Pemberton of Christiansted knew that many present-day bakers are unwittingly, but sacrilegiously, substituting mint jelly for the traditional greengage (also called “green lime”) jam, one of the obligatory layer-toppings of the Crucian Vienna cake, they would turn over in their graves, hold their bellies, and “bawl foh deh mohmmah dem.”

Today, many Crucians believe that a “benye” (pronounced “beneh” by some Frederiksteders) is simply a fried banana bread with a bread-like consistency. That is because they were born long after “Miss Mabel” [Andrews, née Ford] who lived on the corner of New Street and King Cross Street in Frederiksted, had gone to eternal repose in the Frederiksted Cemetery, a stone’s throw from her home on the ground floor of which she made some of the best benyes known to man. What young Crucians do not know is that a correctly made benye is made with yeast, not with baking powder, and has a slightly “elastic” texture, with two of the delicacy’s distinguishing flavors being dried orange peel and ground cloves.

“Don’t know beef from bull foot.”

And to mention “croustades” to a new-age Crucian would be tantamount to speaking Greek: “Crous-what?” would likely be the response. That is because they have never heard of Christiansted’s Zelda Prince, who was the “Croustades Queen,” so much so that in 1974 when sisters Grete and Laurel James, daughters of Gustav and Evelyn James, had their double-wedding at St. Patrick’s Catholic Church with a reception thereafter at the Carlton Hotel, the James family insisted—in spite of the hotel’s top-class chef’s representation that he could duplicate the recipe—that Prince’s croustades be delivered to the hotel’s kitchen, where they would be filled with the chef’s own “chicken à la king” and served during the cocktail hour preceding the wedding banquet.

The authentic Crucian black bread, once an island-wide staple, with its characteristic glazed top crust, has completely—and, apparently, irretrievably—disappeared.

Making “greengage” (also called “green lime”) the old-fashioned way—the way it was made by Mrs. Derricks of Queen Street, Frederiksted—was an arduous, labor-intensive, time-consuming endeavor, the entire process taking two weeks. But today, with modern technology, the delicious jam can be made in two hours’ time, the result being comparable to the old-fashioned way. Yet, the epic associated with the making of “green lime” persists, to the detriment of the preservation of the jam itself and the authenticity of the Crucian Vienna cake for which the jam is a compulsory ingredient.

There are Crucians who cannot distinguish between guavaberry rum and guavaberry liqueur and have never seen a demijohn.

Over the years, excellent recipe books on Crucian cuisine have been published, the most notable being Amy Mackay’s Le Awe Cook; Krusan Nynyam from Mampoo Kitchen by Laura Moorhead; and at least three editions of Native Recipes, published by the University of the Virgin Islands Cooperative Extension Service under the informed guidance of Mrs. Olivia Hinds Henry, widow of Oscar E. Henry. But those cookbooks, written back in the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s are today not as widely known or read as they were when first published. And no comprehensive cookbook on Crucian foods has been published in the 21st century. As such, there are cooks, especially non-native ones, who are cooking pseudo-Crucian dishes, their creations oftentimes the result of eyeballing, blind-tasting, and outside influences. There are cooks, for example, who think Crucian potato stuffing owes its color and sweet flavor to sweet potatoes, and there are others who use instant, powdered potatoes in the name of efficiency but at the expense of authenticity and flavor. Then, to add insult to injury, such cooks typically do not realize that the dish is traditionally baked. Consequently, they serve it like mashed potatoes, but with an ice cream scoop—as if that somehow compensates. Crucian potato stuffing, for the record, is unique to St. Croix. And to Crucians, its ingredients, manner of preparation, flavor, and texture are sacred, any deviation being tantamount to culinary capital sin. Unfortunately, however, there are now two generations of Virgin Islanders who know only the highjacked (and “jacked-up”) “distant cousin” to Crucian potato stuffing.

“Throw-weh sprat foh catch whale.”

The Role of the Agriculture and Food Fair—and other festivals

Towards the end of the Danish era, beginning in the early 1900s, an annual, island-wide, government-sponsored agriculture fair would take place at Estate Anna’s Hope. By the late

1940s, however, the event had faded into the past. But when the event was rescued from the obscurity of time in 1971 by the Virgin Islands Department of Agriculture at Estate Lower Love, its focus was not only agriculture, but also food. Eventually, the event officially became the Agriculture and Food Fair. And it is at the Agriculture and Food Fair that it is possible to experience some of St. Croix’s best food, but, unfortunately, also some of its worst. Yes, people who know authentic Crucian food will know which cooks and organizations to seek out: Gloria Joseph for her red peas soup and kallaloo; “Cino” Christopher for his roasted pork and salt-fish rice; Renita Johannes for her cream cake; the Doward family of Frederiksted for pâtés and seasoned rice; the Moravian Church for crab-and-rice, maufé, and banana fritters; Betty Lynch for her boiled fish with fungi and her seafood salad; the Christian family of Frederiksted for roasted goat and potato stuffing; the Pembertons of Christiansted for souse and potato salad and fried fish with johnny cake; etc. But for the average fair attendee, who does not know the island’s “cooking-families,” the entire “Ag Fair” food experience is one of hit-or-miss.

While the three-day event, held during Presidents’ Day weekend and dubbed “the largest agriculture and food fair in the Caribbean,” is an excellent opportunity for vendors, the vast majority of the food offered for sale serves to discredit true Crucian cuisine. And while in a free enterprise system every qualified food vendor should be able to offer his products for sale, the organizers of the event also have an obligation to preserve and showcase St. Croix culinary heritage in its truest expression.

As such, there has long been expressed a need for the establishment of an “Authentic Crucian Food Pavilion”—whether under a tent or in a designated building—for the showcasing of authentic Crucian cuisine where food vendors would have to pre-qualify before a panel of judges versed in Crucian cooking prior to being allowed to offer specific traditional items for sale. A vendor may qualify for selling kallaloo in that pavilion, for example, but not pâté or maufé if those two items do not meet the judges’ standards. Or a vendor’s maubi might meet the standards, while his benye does not. The aim of such a system would be to ensure that, regardless of what is being sold elsewhere on the fairgrounds, patrons of the Authentic Crucian Food Pavilion would be reasonably assured that the food being offered for sale therein meets certain authenticity guarantees.

[Crucians cooks and connoisseurs of local cuisine such as the late Eileen M. Messer (1913-1996), admired for her kallaloo, maufé, and cream cake; Maria Edwards [Gibbs] Pinder, who, despite retiring years ago, remains sought-after by Christiansteders for her butter cookies, kallaloo, and red grout; the late Winifred Stevens Ellis (1921-2001), wife of the late Vernon Ellis and mother of Crucian joiner Vegan Ellis, a specialist of sweetbread, tarts, and red peas soup; Lena Abel Schulterbrandt, daughter of Crucian joiner Arthur Abel and herself an expert judge of correct Crucian cooking; the late Veronica Williams Frorup (1935-2015), who year after year volunteered as a food judge at the Ag Fair; the late Jessica Tutein Mooleanaar (1925-2002), an excellent cook of maufé and maker of roast-fish brine; Denise Hennemann Ellis, an expert in local pastries, especially sweetbread; the late Agnes Agatha Samuel (1936-2014), locally famous for her pound cake and peas-and-rice; Eleanor Sealey, who devoted many of her years to cooking for some of the island’s most discerning families; the late Violet “Aggie” Armstrong Bough (1929-2006), a connoisseur of Crucian culture; the late Felicita James García (1911-2004), who, for years, baked cakes, local breads twice per day in her brick oven (which still stands), and provided catering services to Christiansted’s elite households; Sharon Braffith, staunch Crucian and longtime organizer of the food vendors at the Ag Fair; Janet Brow, a devoted connoisseur of Crucian cuisine who each year helps to prepare the bull for “Bull and Bread Day”; and Amy Blackwood, descendent of Amy Mackay, the great Crucian cook, are/were excellent arbiters of traditional Crucian cuisine.]

The Other Major Culinary Events

The Festival Village

St. Croix’s carnival occurs during the Christmas holidays. And one of the primary events is a food fair that takes place in the vegetable markets of Christiansted and Frederiksted. Then, for a period spanning almost two weeks, local cooks sell food from booths in the “festival village.” But as is the case with the Agriculture and Food Fair, in order to be assured of authentic Crucian cuisine, one must know the various cooks and seek out their specialties, booth by booth, otherwise one is liable to purchase pseudo-Crucian cuisine.

The Crucian Puerto Rican All Ah We Tramp and Breakfast

But as Crucians say, “When you say, ‘one,’ you have to say, ‘two.’” And that said, one of the absolute best culinary traditions of St. Croix—one where authentic Crucian food is sure to be served—is the annual “Crucian Puerto Rican All Ah We Tramp and Breakfast,” which culminates at the Christian “Shan” Hendricks Market on Company Street in Christiansted immediately after the ‘fo’ deh mahnin’ Stanley and the Ten Sleepless Knights scratchband serenade, which begins in the parking lot of the Golden Rock Shopping Center and ends at the market.

All the food and drink at that event are served compliments of the various cooks. And some of the island’s best cooks and cooking-families, as a Christmas gift of food and drink to the people of St. Croix, prepare traditional breakfast dishes—whether salt-fish and dumplings; or smoked-herring gundi with avocado and a slice of buttered bread; or fried fish (especially “jacks”) and johnny cakes; or canned sardines and boiled cassava; or salt-fish gundi with sweet potato; or a bowlful of “cornmeal pop,” for example—and serve their specialties, free of charge, to one and all.

On the morning of the Crucian Breakfast, everyone is on good behavior, similar to the way people conduct themselves at a church picnic or when visiting the native areas of the sister island of St. John. The event attracts members of the oldest and staunchest Crucian families, as if an annual, all-island family reunion: Acoy, Cornelius, Johannes, Smith, and Charles of La Vallée; Byron and Hurley of Estate Grove Place; Drummond and Ballantine of Calquohoun and Mon Bijou; Tutein, Encarnación, McGregor, Larsen, and Hansen of Gallows Bay; Farrelly, Henderson, Benjamin, and Bailey of Frederiksted; Frorup, Behagen, Golden, and Whitehead of Christiansted; the “Cane-Ratta” clan, and the “Yamba-Dog” clan.

Surnames such as Hennemann, Pedro (locally pronounced “Pee-dro”), Allick, McInosh, Lucas, Lenhardt, Schraeder, Adams, Jacobs, Prince, Schade, and McBean are always present at the event.

Members of the Brignoni, Cariño, Suárez, Santos, Monell, Camacho, Rodriguez, and Bermudez families are always well-represented.

The Roebucks of Solitude; the Jameses of La Grange; the Clarkes of Wheel of Fortune; the Tranbergs of Nicholas; the Bradys of Caledonia; and the Schusters of Bonne Esperance are always sure to attend in large numbers.

Members of the Heyliger, Messer, Hector, Ritter, Rissing, Hardcastle, Andrews, Johansen, Brannigan, Ovesen, Rivera, Soto, McAlpin, Dowdy, Christensen, Nielsen, Martinez, Iles, Fredericksen, Hørsford, Petersen, Lindqvist, Lindquist, Gomez, Stridiron, Coulter, Merwin, Clendinen, O’Bryan, O’Reilly, Ramirez, Lawaetz, Isaac, Ford, Fabio, Bølling, Pretto, Brodhurst, Nelthropp, Hardcastle, Hodge, Canegata, Ruan, Gardine, Skeoch, Ross, Moorhead, Flemming, Dunbavin, Pentheny, Velásquez, Durant, Bauman, Bowman, Hendrickson, Mackay, Grigg, Nico, Knight, Schjang, McFarlane, Bough, Pedersen, de Chabert, Brow, Dyer, Skov, Forbes, Hughes, Neazer, Sarauw, Peterson, Sargeant, Begraff, Schouten, Jeppesen, Steele, Ebbesen, Phaire, Thurland, Peña, Hall, Pitterson, Lang, Todmann, Jensen, Finch, Coff, Lovgren, Nicholson, Simmelkjer, and Sheen customarily attend the breakfast.

Last names such as Harris, Harrison, Sackey, Morales, Lockhart, Nieves, Carrington, Oliver, Gereau, Rogers, Greenidge, Mason, Bishop, Armstrong, Espinosa, Frederiks, Christian, Gaskin, George, Ayala, Emmanuel, Krauser, Samuel, Powliss, Estick, Huggins, Petrus, Bennerson, Schraeder, Arnold, García, Bastian, Williams, Todman, Evans, Anduze, Harrigan, Joseph, Cabret, Gibbs, John, Rios, Abel, Jackson, and Matthias are always represented at the great event.

Offering food and tasting food at the breakfast are always members of the Christiansen, Bryan, Motta, Edney, Parris, Miller, Tuitt, Hewitt, Gittens, Pemberton, Rodgers, Aponte, Saldaña, Richards, Henry, Powell, Franklin, Edwards, La Motta, King, Phillipus, Santiago, Howell, Urgent, Krieger, Davila, Griles, Milligan, Braffith, Quiñones, Doward, Bruce, and Hendricks families.

Abramson, Simmonds, Vickers, Eastman, Dowling, Duval, Simmons, Benjamin, Solomon, Belardo, Brown, Gill, Canton, Gerard, Francis, Seales, Ramirez, Sealey, Martin, Roberts, González, Krigger, Bess, Marshall, Springer, Chase, Burke, Willocks, Brooks, Kiture, Doute, Barry, Fawkes, Jimenez, Heywood, Dompierre, Correa, Moorehead, Felix, Carter, Davis, Barnes, Leacock, Ellis, Lawrence, Thompson, Plaskett, Bentick, Prentice, Johnson, Rohlsen, Figueroa, Stevens, Ortiz, and Lynch are some of the Crucian, Puerto Rican, and Crucian-Puerto Rican families that religiously attend the breakfast.

For those several hours, until about midday, spoken or unspoken differences are set aside; friends embrace; normally guarded bottles of precious, homemade guavaberry rum are opened and generously poured; people who have not seen each other for years greet each other with profound warmth; Crucians inquire as to each other’s family, the way they always did in times past; friends and lovers taste from each other’s plates and sip from each other’s cups. The air is perfumed with the delicate aromas of “bush” teas: lemon grass; “balsam” (basil); soursop; mint; hibiscus. The food is cooked and served with love. And that love is both palpable and palatable. Hands down, the event is one of the island’s most beautiful. To attend it is to experience Old Santa Cruz.

“Cockroach ain’t nebba got no business in fowl coop.”

(The Typical Crucian Breakfast)

To observe the components of a traditional Crucian breakfast is to observe the culture from which it derives. Until the arrival of Harvey Aluminum and the Hess Oil Refinery in the mid-1960s, St. Croix was primarily an agrarian society. And to undertake the arduous task of working the land from sunrise to sunset, it was necessary for laborers to begin the day with a solid meal that would sustain them until lunchtime. And because the agricultural workday begins early, it was more practical for that solid meal to be, in effect, leftover dinner. Salt-fish in butter sauce with boiled green figs for dinner became salt fish in butter sauce with boiled green figs for breakfast. Thus, the traditional Crucian breakfast—and traditional breakfasts throughout the Caribbean region—was born. And though St. Croix’s way of life has transitioned from agrarian to industrial and commercial, the traditional breakfast has endured. Until the coming to the island of packaged instant breakfast cereals such as Kellogg’s Corn Flakes (established in 1894) in the late 1960s, school-age children traditionally ate “cornmeal pop” (a cornmeal porridge that is the maize-equivalent of grits), cream of wheat, or oats, cornmeal pop being the most commonly served.

(“Bush” Teas)

Unlike the Spanish Caribbean, where coffee is the morning beverage, on St. Croix, the traditional breakfast drink has always been herbal teas, locally referred to as “bush” teas, with “cocoa tea” (called “hot chocolate’ in the mainland USA) a distant second choice. “Bush” teas are usually made from freshly picked herbs that are steeped, rather than boiled, in hot water. (Just as provision plots served as a garden for the growing of tubers and vegetables, aromatic, culinary, and medicinal herbs were also grown on the plots. And because of the easy access to the fresh herbs, the use of dried tea leaves, as is the case in many tea-drinking cultures, was never the common practice on St. Croix).

Practically every native herb has medicinal value if used correctly. But the herbs that are used for making teas tend to have pleasing aromas and taste in addition to their therapeutic qualities. The petals of the classic, simple, red hibiscus flower, when steeped in hot water and flavored with fresh lime juice and sugar, make a delicious, ruby-red tea, its flavor hinting of berries and spices. The fresh or dried leaves of the soursop tree and the bay leaf (laurel) tree are boiled, not steeped, to produce two of the island’s favorite breakfast teas, though soursop tea is widely believed to be a sedative. Lemon grass, fresh or dried, is steeped in hot water, the result being a beautiful golden-yellow tea with an emphatic citrus flavor. The plump leaves of “Spanish thyme” make a highly aromatic, flavorful tea. Then, of course, teas are drawn from fresh mint and basil leaves.

Mango Melee

Established in 1996 and held annually in July at the breathtakingly beautiful St. Croix Botanical Garden, Mango Melee has evolved into one of the most anticipated food events of St. Croix.

The parameters of Crucian food are generally very defined and rigid: souse must contain onions and celery, but never green peppers; and to the outsider, kallaloo might look like a dish that would likely contain onions, green peppers, and garlic, but to include those ingredients in Crucian kallaloo would be a culinary crime of epic proportions.